News for the East Bay's diverse, working-class majority.

Brought to you by the Democratic Socialists of America, East Bay chapter.

September 23, 2019

East Bay bus drivers are ready to strike to save public transit

Scene from the Oakland general strike of 1946, in which transit workers played a central role. Credit: Oakland Museum of California

By Richard Marcantonio

East Bay bus drivers and mechanics voted overwhelmingly on Sept. 7 to authorize a strike against AC Transit. The strike by members of Amalgamated Transit Union, Local 192 (ATU 192) could start as early as October. AC Transit bus riders, who have suffered years of service cuts and fare hikes, share a common interest with these transit workers.

Both riders and workers need to stand up together against corporate greed to demand a fully funded transit system that provides reliable transportation to all. ATU 192 has historically stood with bus riders, and its looming strike will write the next chapter in that struggle.

ATU 192 and transit riders: A history of shared struggle

Before the California legislature created AC Transit as a public transit system in 1960, the East Bay’s transit network was called the Key System. It was privately owned and run for profit by the real estate speculators who were building the East Bay. ATU 192’s predecessor union represented the conductors and motormen of the Key System.

The streetcar workers of Division 192 played a “central role” in the Oakland General Strike of 1946, writes Kafui Attoh in “Rights in Transit,” his new book detailing the history of East Bay transportation struggles. “[W]hat had begun as a minor strike of department store workers exploded into a city-wide crisis with more than a hundred thousand workers refusing to clock in.”

The general strike, in turn, catalyzed a far-reaching set of working-class demands, when “labor unions like the ATU 192 joined with the Oakland Voters League to support one of the most progressive platforms in the city’s electoral history.” That platform included many proposals, such as a repeal of a regressive city sales tax, a call to maintain local rent control, and to increase funding for public schools. It also included “a call to study the possibility of establishing a publicly owned transit system.”

The creation of a publicly owned transit system received a decisive push just a few years later, when ATU 192 struck the Key System in 1953. The strike lasted more than two months, and Attoh notes evidence of a high “degree of solidarity and public support for striking workers.” That strike “galvanized much of the skepticism already attached to the Key System into a popular push for public ownership [and] by the fall of 1960, the East Bay had its own publicly owned transit system.”

That public system, AC Transit, was unusual in having a democratically elected board. By the late 1970s, it was running robust and affordable bus service from Fremont in the south to Richmond in the north, and transbay service between the East Bay and San Francisco.

Austerity, racism, and privatization plague AC Transit

The slow but steady destruction of the public bus system won by working-class struggle has been the result of austerity politics, the corporate agenda to create a “separate and unequal” transit system and, most recently, the privatizing assault of “transportation network companies” like Uber and Lyft, which have eroded transit ridership and revenues all over the country.

Public disinvestment began in 1978, with the passage of Proposition 13 in California and its cap on property tax rates. “Following the passage of Proposition 13, [AC Transit] lost $17 million in subsidies,” leading to deep service cuts. By the late 1990s, in an explicit attack on both unionized workers and transit riders, the Clinton administration had zeroed out most federal subsidies to operate transit, further decimating urban bus service nationally.

While the public bus system was being squeezed by austerity, Bay Area corporate CEOs, organized as the Bay Area Council, were aggressively promoting their post-War plan to create the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system. A 1977 report emphasized that these CEOs paid scant attention to the needs of low-income communities of color. “Although low-income persons and minorities make up a large proportion of the residents in 21 of BART’s 34 station areas, the system does not provide significant travel time savings for them,” the study found. “Buses served most of these areas before BART service began, and they have continued to provide service.”

Attoh similarly notes that the Bay Area Council’s

“imprint on BART … extended to the design itself. BART’s focus on downtown San Francisco, its obliviousness to the transportation needs of more working-class residents, and its failure to stem the tide of private automobiles were … all by design. Such features simply reflected BART’s ostensible purpose — to boost the values of downtown properties held by [the Bay Area Council’s corporate members] themselves.”

Swayed by this powerful lobby, the region’s transportation funding agency, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) prioritized massive public resources for the construction and expansion and BART. That single-minded priority came at the cost of starving bus service. It led to stark segregation in transit, while also planting the seeds for gentrification and displacement around BART stations in historically redlined communities like East, Oakland, West Oakland, and Richmond.

ATU 192 and bus riders fight back

By 2005, AC Transit was a “separate and unequal” system, serving a ridership that was nearly 80 percent people of color and very low-income. Its riders also disproportionately included seniors and people with disabilities and middle- and high-school students, for whom the public bus serves as the “yellow school bus” in most East Bay school districts.

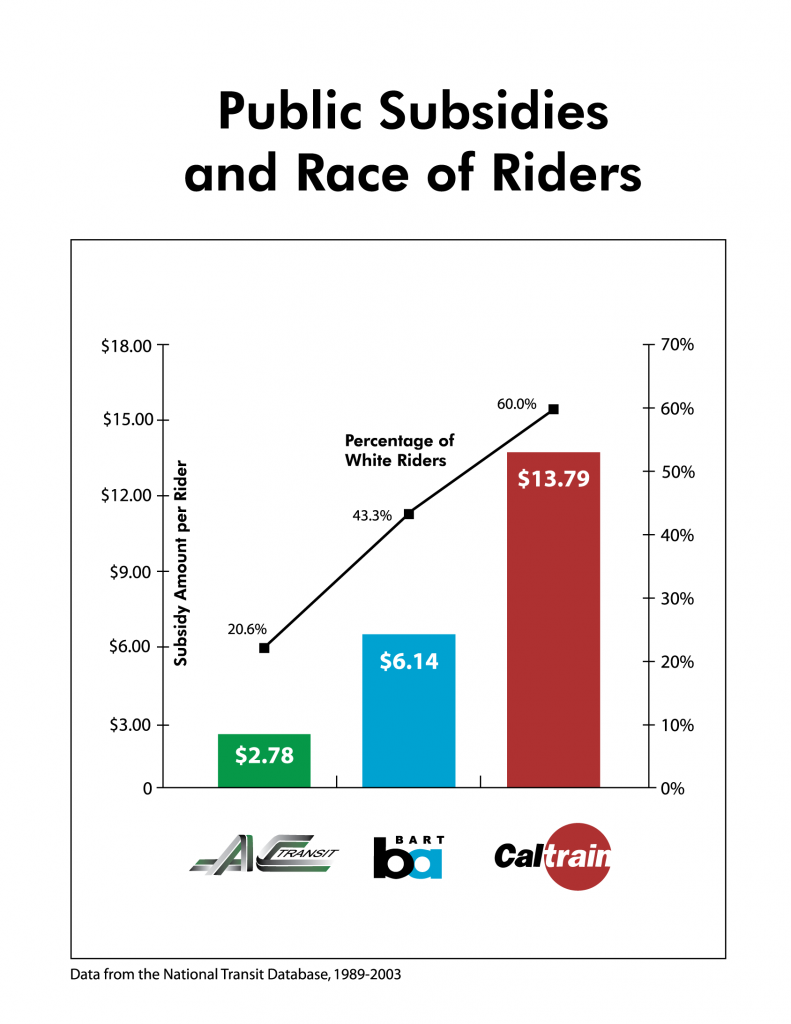

In April of that year, ATU 192 joined bus rider Sylvia Darensburg, representing a plaintiff class of AC Transit riders of color, in a federal civil rights lawsuit against the MTC. The complaint alleged that the MTC had long channeled funds to expand service for “the disproportionately white riders of Caltrain and BART, at the expense of the disproportionately minority riders of AC Transit,” as demonstrated by a public subsidy per rider that varied according to the share of white riders on each of the three systems.

At trial, ATU 192 and the plaintiff class demonstrated that nearly 95% of all funding in MTC’s multi-billion dollar transit expansion program went to rail projects — mostly expansions of BART to suburbs, San Jose and the Oakland airport favored by the Bay Area Council — while less than 5% went to bus projects. While the case did not succeed in the face of obstacles imposed by federal law and the judicial system, ATU 192’s advocacy on behalf of the shared interests of its transit-worker members and the riders they serve demonstrated that its commitment to the common good, dating back to the Oakland General Strike and the founding of AC Transit, remained alive and well.

If the history of shared struggle between the workers of ATU 192 and the riders they serve is any guide, the lead up to a potential strike this fall will be another front in the fight to save public transit. Part of a larger fight against the austerity and privatization imposed by corporate elites and billionaire investors, it could reverberate far beyond the East Bay.